Behavioural scientist and author of The Choice Factory, Richard Shotton, explores how brands can harness the power of public statements to build trust.

“Well, they would say that wouldn’t they?”

Perhaps advertising’s biggest challenge is what I would call the Mandy Rice-Davies problem.

Not familiar with Mandy? Well, let me give you a bit of background. It’ll only be a small digression.

Rice-Davies was a bit player in the Profumo affair, the sex scandal that brought down Harold Macmillan’s government in 1963.

The scandal erupted when the press discovered that John Profumo, the married Secretary of State for War, had been sleeping with a showgirl, Christine Keeler. Unfortunately, for both Profumo’s career and Britain’s defence secrets, Keeler was seeing another man at the same time Yevgeny Ivanov, a Russian spy.

The situation descended into an almighty set of recriminations, culminating in the trial of one of Profumo’s associates who was accused of “living off immoral earnings”. Mandy Rice-Davies, a good friend of Keeler, was called as a witness.

At the trial, the defence counsel* was intent on discrediting Rice-Davies. He tried to pit her word against the illustrious Lord Astor, who swore that he hadn’t met her, let alone slept with her.

When told of Astor’s denials, she giggled back, “Well he would say that, wouldn’t he?” **

Her answer was the most famous moment of the trial.

It captured something of the zeitgeist, a crumbling deference to the old elite, but also a broader idea - that it pays to be sceptical of claims from people with strong vested interests.

And that brings us back to advertising.

Soho: we have a problem

While many brands would like consumers to pliantly accept what they say, that has never been the case. Consumers know that brands have a vested interest in positively spinning the truth. So, they react to advertising’s grandiose claims, by thinking, “well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?”.

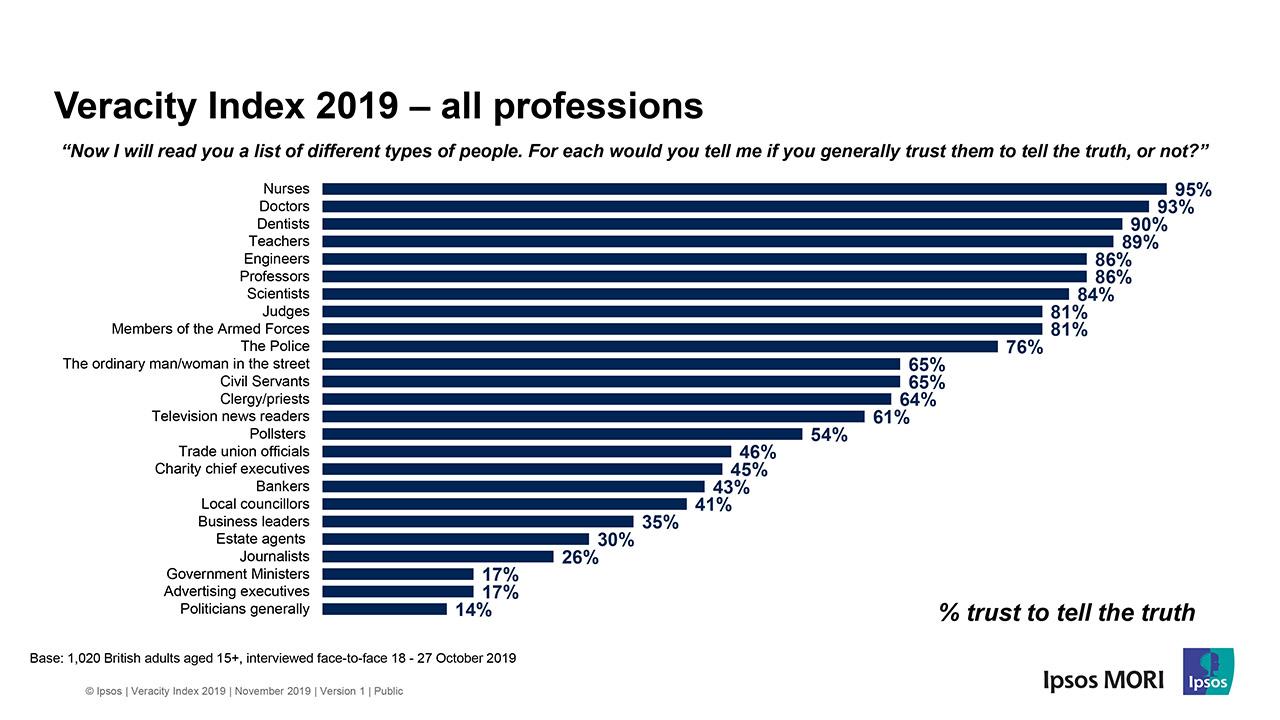

That’s not speculation. Consider IPSOS’s latest research on trust. The key chart is shown below: in terms of trustworthiness, advertisers are ranked 24th of the 25 professions studied. Even more damning, estate agents are almost twice as trusted!

If believability is the problem, what’s the solution?

Let’s start with what won’t boost trust. You can’t claim to be trustworthy and expect that to work. A sinner and a saint will both claim to be honest. It’s a meaningless statement.

What you need is something that screens out the rogues. A tactic that only the honest will adopt.

There are a couple of approaches that you could use, but I want to focus on one – the power of public statements.

I’ve run a few studies which suggest that the same statement has a different effect dependent on whether it’s made publicly or privately.

In my first experiment I asked participants to imagine that their MP made a spending pledge. Sometimes I told them it was made one-to-one, sometimes at a public meeting. In the private setting, roughly 40% thought the promise would be broken – but that dropped to just 20% in the public setting.

Politicians are a strange breed, so I recently re-ran the thought experiment in a different setting. I asked 269 people to imagine that they had lent a colleague a tenner. Then I asked them the likelihood of being paid back on time.

The proportion who thought it highly likely they’d be paid back promptly was 43% higher if the commitment had been made publicly rather than privately.

Both these studies reveal that claims made in public are more trusted. People understand that there will be a greater loss of face if a publicly stated promise is broken, compared to a private one. It’s not that we think the politician or colleague become any more moral, but that their self-interest compels them to be a little more truthful.

The advertising application

But what’s this got to do with advertising? Well, it suggests that claims made by an advertiser are more trusted if they’re made in public, on a broadcast medium, rather than on a targeted, one to one medium.

Ah, you might say, but doesn’t that depend on the public being attuned to the intricacies of media. Is that realistic?

Bob Hoffman, the Ad Contrarian, seems to think so. He states:

“Most people are pretty good behavioural economists. They may not know anything about how the products they buy work, but they know how to read the advertising signals… They know how and where quality brands advertise and what advertising for quality brands feels like. And they also know where shitty brands advertise.”

Again, the data supports this point. I asked 257 people to imagine that they saw an ad for a chocolate bar online. How many other people did they think had seen that ad? Only 46% thought that more than a million people would have seen it. That figure increased to 71% if they were told the ad appeared on TV.

People pick up on the body language of an ad. They recognise what’s a public statement and what’s a private one. And they’re more likely to trust public ones.

Mandy Rice-Davies applied

So, if you’re interested in persuasion, remember Mandy Rice-Davies. You can’t assume that your audience will believe what you’re saying. But you can boost the chances of being trusted by harnessing the power of public statements.

Ironically, this seems to be the opposite of how advertisers are behaving. In the medium-term brands have been turning to more personalised, targeted media. In the short-term, during the COVID outbreak, some brands have pulled back even more glaringly and stopped their paid-for advertising and instead relied on their CRM.

The danger is audiences will react by saying, “well they would say that, wouldn’t they”.

*Intriguingly, the defence counsel, James Burge, was John Mortimer’s inspiration for the TV barrister, Rumpole of the Bailey

**The pedants out there might be harrumphing here. What she actually said was “Well he would, wouldn’t he”. However, the press reportedly it differently and the iconic phrase was born.

Thinkbox

Thinkbox